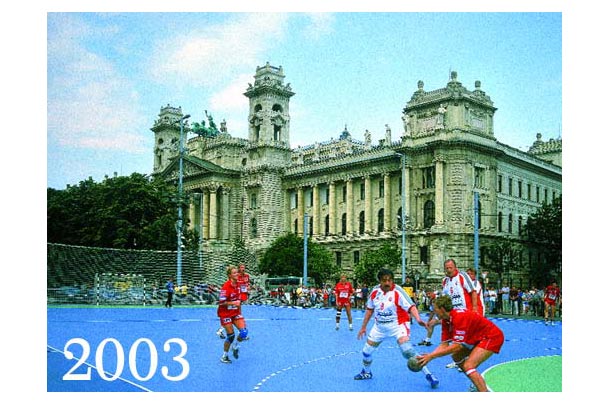

Parliament Building: History's only violent revolution against Soviet communism began in October, when hundreds of thousands of students and disaffected Communist Party members took to the streets calling for an end to Stalinist rule. On Nov. 4, Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest. They departed Hungary for good in 1991

A young poet was running through the corridors of the university asking who wanted a submachine gun. I thought it better to have one. I kept it under my bed. We were the national guard, about 2,000 of us, the armed wing of the reform government.

My job was to guard a psychology professor who the leadership said was very precious to them. We had meetings at the writer's union with the respected elder writers. They played a kind of advisory role. One older writer was invited by the workers to a trade union meeting and was asked: 'What should we do?' He was very slow. He scratched his chin. 'Continue,' he said. They continued.

There was a box outside the West Railroad station marked "for the wounded." It filled up with money and no one stole it. On Nov. 4, it rained and the money was destroyed. I had crazy moments when I believed that maybe some terror would be appropriate against the collaborators, because the Russians were many and the collaborators fewer.

I went out to see who I could shoot but could not, somehow, imagine it. I was in bed with my wife on the morning of Nov. 4 [when the Soviet tanks returned]. I could hear cannon fire. I got my submachine gun and went to the war. I went to the university.

There were people who were so full of enthusiasm. One came and asked us to go with him because the Russians were firing on their position. I said, 'Why?' He said: 'Because we are being shot at.' 'Just to be shot at?' I said. 'Yes,' he said, 'but to be shot at together.'

It was beautiful and heroic, but there was a lesson in 1956. Bloodshed put the Soviets in a corner. Slow, steady political work in the end was more efficient.

Gyorgy Konrad is a novelist and essayist whose writings were banned by the communists as politically subversive

BALAZS GARDI / PANOS FOR TIME

BALAZS GARDI / PANOS FOR TIME